Imagine, if you will, a world without Kelso (1957), Northern Dancer (1961), Sunday Silence (1986) or Frankel (2008) — all of whom trace back directly to Mahmoud.

Of course, the overwhelming presence of Mahmoud in the pedigrees of thoroughbreds worldwide is linked to his most potent descendent: Northern Dancer. But without Mahmoud, there could never have been a Northern Dancer. And although the matter of analyzing the gene cocktail that produces a thoroughbred remains a mysterious affair, what Mahmoud contributed to his progeny — and their descendants — had the kind of impact that tells us it was significant.

Yet Mahmoud’s story is punctuated by the dawn of a modern, mechanistic sensibility: his inconsistency on the turf made him suspect, as did his colour — in the 1930’s the thoroughbred community were still spooked by a grey horse, believing that this “off” colour indicated a lack of stamina. His size and bloodlines were called into question repeatedly when his performances fell short. And after his greatest victory on the turf, the feeling was that he’d stolen the win from far better horses or that he was lucky in running against a weak field.

Dismissed by the experts of his day, H.H. the Aga Khan III’s little grey champion “went viral” long before the concept swept the twenty-first century…..in the breeding shed.

Let’s face it: we’re in a hurry to have champions. Perhaps it was always thus. But now we have a vast social media that allows us to transmit our desire and frustration minute-by-minute. That same media has also altered our sense of time: specifically whether it’s moving fast enough to suit us. The other thing about time as we know it is its persistent connection to productivity through a history of industry that gave us the prevalent metaphor of the last century: the machine. Even the mighty Secretariat, who was so much more, inherited our associations between perfection and mechanics, as in the phrase that defines his astounding victory at Belmont: “Secretariat is widening now…he’s moving like a tremendous machine.”

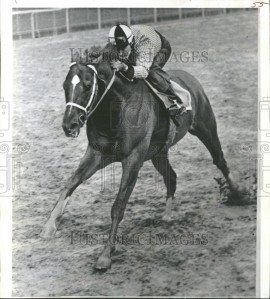

SECRETARIAT with Ronnie Turcotte in a work over “big sandy” before the colt’s run in the Belmont Stakes. Bob Ehalt was there and struggled to find a way to describe what he’d seen. Finally he came up with his own imagery for an amazing colt who “…ran a hole in the wind.” Photo and copyright, The Chicago Tribune.

But the thing about machines is that they’re not alive, despite the fact that they might seem to be, and that is why they are consistent, economical and flawless (at least most of the time) in a production line.

Horses march to a different rhythm. In the case of the thoroughbred, progress (i.e. success) isn’t automatically connected with the passage of time and even when it appears to be, it’s often flawed. And, as we’ve learned over and over again, great thoroughbreds don’t reproduce themselves with the kind of speed and consistency that our modern sensibilities expect.

The story of Mahmoud sounds a cautionary note about this kind of thinking, since by today’s standards the pony-sized grey would have very likely known a similar fate to that of the brilliant Smarty Jones, whose inability to turn straw into gold in the first few years of his breeding career still echoes loud in the minds of those of us who think he has phenomenal stallion potential. (Smarty’s potential has already borne fruit, notably in the star Japanese fillies Keiai Gerbera [2006] and Better Life [2008], as well as a dozen other very good individuals who have raced in the Northern Hemisphere.)

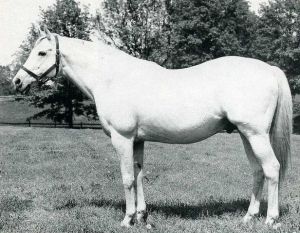

SMARTY JONES pictured in Uruguay. A thoroughbred with the heart of a true champion, SMARTY failed to reproduce himself quickly enough for an impatient American market. But he may yet have the last laugh, as his current progeny record indicates.

Champion BETTER LIFE earned over a million dollars racing in Japan, where she defeated colts as well as fillies and built an enormous fan base.

The breeding acumen of H.H. The Aga Khan III was remarkable. Although he started out in life as a man of modest means, the Aga proved to be a shrewd businessman, as well as a very progressive religious leader of his people. And when his wealth allowed him to purchase the best bloodstock, the Aga solicited the help of the equally brilliant George Lambton*, younger brother of the Earl of Durham. It was this alliance that would bring Mahmoud into the world.

1930 — Blenheim wins Epsom Derby (with sound)

A son of Blenheim II, Mahmoud’s dam was Mah Mahal (1928), a daughter of the incomparable Mumtaz Mahal (1921), who had been purchased as a yearling by Lambton in 1922 for the Aga’s stables. The arrival of the filly who would come to be known by the British racing public as “The Flying Filly” would have an enormous impact on the Aga’s breeding fortunes, as well as on the evolution of the modern thoroughbred. All of her offspring were very good, but it was through her daughters that Mumtaz Mahal assured her legacy. They accounted for the champion Abernant (1946), the great sire Nasrullah(1940) whose contribution to the American thoroughbred was arguably as vast as that of his grandam, the champion Bashir (1937) who raced in India and Migoli (1944), winner of the Arc and sire of the American champion, Gallant Man (1954). And scores of brilliant thoroughbreds issued from these: among them, the European champion, Petite Etoile(1956), Bold Ruler (1954) and his greatest son, Secretariat (1970), as well as a granddaughter who is still considered the Queen of American racing, Ruffian (1972).

Too, the legacy of Mumtaz Mahal would gradually teach a skeptical racing public that there was nothing inferior about grey thoroughbreds.

The Aga Khan’s BLENHEIM II, sire of MAHMOUD and Triple Crown winner, WHIRLAWAY (1938), as well as JET PILOT (1944) and champion filly A GLEAM (1949). BLENHEIM II was also the BM sire of a bevy of champions, including PONDER (1946), HILL GAIL (1949) and KAUAI KING (1963).

Mumtaz Mahal was a daughter of one of the finest thoroughbreds ever bred, The Tetrarch (1911). Like Mahmoud, the presence of The Tetrarch in the pedigrees of thoroughbreds all over the world today remains significant, particularly given that he only raced as a two year-old before being retired to stud, where he was plagued by fertility problems.

The brilliant MUMTAZ MAHAL was dubbed “The Flying Filly” by British racegoers. Painting by Lionel Edwards.

THE TETRARCH was selected one of the best thoroughbreds of the last century, even though he only raced for a single season. Ridiculed for his markings (“chubari spots”), THE TETRARCH would have the last laugh by becoming a prepotent sire and BM sire.

Mahmoud’s BM sire was Gainsborough (1921), winner of the British Triple Crown and sire of another individual who would change the face of thoroughbred breeding forever, Hyperion (1930). Mah Mahal’s first born had indeed been the issue of the best on both sides of his pedigree, a practice the Aga considered axiomatic in the making of a champion.

The handsome GAINSBOROUGH, winner of the British Triple Crown and grandsire of MAHMOUD. GAINSBOROUGH is also — famously — the sire of HYPERION (1930).

Mah Mahal’s tiny grey colt had a lovely Arabian look about him, but given his size as a yearling, he was deemed too small and sent off to auction at Deauville in France. When the colt failed to reach his reserve, the Aga decided to keep him. As a breeder, His Highness was without sentiment. Any animal out of his stables who appeared ill-equipped to build a legacy was discharged to the sales. Nor was he moved to keep horses who proved their worth if he received a suitable offer of purchase; the result was that several of his champions found their way to America’s shores.

Although he doubted that Mah Mahal’s first born would ever amount to much, the Aga was disinclined to give the colt away for less than he was worth. So Mahmoud was sent off to Newmarket to be trained by Frank Butters, in the hopes that he would be decent on the turf, if not brilliant. An Austrian by birth, Butters settled in England where he became a leading trainer first for Lord Derby and then for the Aga. Butters enjoyed a fabulous career, his very best horses being Fairway (sire of Fair Trial among others), Beam (winner of the 1927 Oaks), Bahram (English Triple Crown winner) and Migoli (winner of the 1948 Arc).

FRANK BUTTERS trained no less than 15 classic winners for clients like Lord Derby and HH the Aga Khan III.

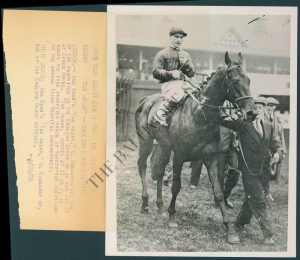

MAHMOUD goes to work with two other more promising colts in the Aga’s stable, BALA HISSAR (1933) and TAJ AKBAR (1933). Photo and copyright, The Chicago Tribune.

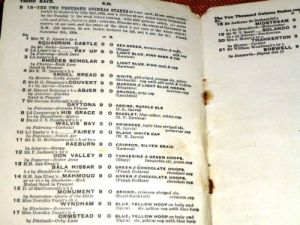

Little Mahmoud’s first start at two was considered void when the majority of the field failed to notice a false start and ran the full course anyway. His next start was in the Norfolk Stakes, where he finished third. He then went on to win his next three starts, which made the press sit up and take notice of the diminutive grey who seemed to skim over the ground as he moved to the front of the field. Mahmoud may have been compact, but he was incredibly light on his feet, allowing him to jettison away when hitting his top speed. (Interestingly, his descendant Northern Dancer would run in exactly the same fashion.) Confirmed as the best two year-old of the season, Mahmoud’s final start came in the Middle Park Stakes at Newmarket. In 1935, the race was considered the most prestigious for juveniles, so when Mahmoud only managed to finish third, beaten over two lengths by Abjer (1933) and Dorothy Paget’s Wyndham (1933), his stamina was called into question. No-one cared that he’d rallied to finish well after getting off to a disastrous start. The thinking was that the Aga’s plucky colt wouldn’t stay the distance, for either the Derby or the 2000 Guineas.

A close-up of MAHMOUD on his way to post. In this shot, next to his even tinier groom, the colt looks much bigger than his 15.3 h. Photo and copyright, The Baltimore Sun.

The legendary Charlie Smirke had been in the saddle when Mahmoud lost the Middle Park Stakes. Smirke had been the Aga’s second string jockey until a racing injury that same year forced Freddy Fox to step down as the stables’ premier rider. Smirke was then promoted to head jockey, much to the irritation of trainer Butters, who, according to various sources, found the outspoken, happy-go-lucky Smirke an irritation. So it was that Mahmoud’s three year-old campaign was punctuated by the disgruntled, though brilliant, trainer’s attempts to keep Smirke off the colts he deemed the best, namely Bala Hissar and Taj Akbar. Butters’ preference was for another legend-in-the-making, Gordon Richards, considered by Smirke to be his foremost rival in the hunt for racing laurels.

TAJ AKBAR shown here with SIR GORDON RICHARDS in the saddle was one of the 1936 Derby favourites. He is shown here following his win in the Chester Vase. (A pity that the press couldn’t get his name quite right!) A fine colt in his own right, TAJ AKBAR would beat the American Triple Crown winner, OMAHA, in the Princess of Wales Stakes in July 1936 at Newmarket. Photo and copyright, The Baltimore Sun.

For the 2000 Guineas, Smirke chose to ride Bala Hissar. His choice may have been based on the fact that his previous ride on the two year-old Mahmoud — who was also entered — had been less than satisfactory, or that the little grey had only managed a fifth place in a previous race, the first of his three year-old season. Steve Donoghue, the top jockey of the first two decades of the twentieth century and now a fifty-one year-old veteran, was engaged to ride Mahmoud. Donoghue was the most beloved of jockeys, following in the footsteps of Fred Archer, and he remains today the only jockey to win the British Triple Crown twice, first on Pommern(1912) in 1915 and then on Gay Crusader (1914) two years later.

As it was to turn out, Smirke and Bala Hissar managed little. But Mahmoud, under the guidance of a master jockey, lost by only a short head to Lord Astor’s Pay Up (1933), a colt who had drawn a post on the far outside of the field and who had entered the Guineas as a true “dark horse.” However, Mahmoud had lost ground getting out of a packed group of horses during the race and in Donoghue’s mind it was this that accounted for his colt’s narrow defeat.

Lord Astor’s PAY UP, the winner of the 1936 Two Thousand Guineas. Photo and copyright The Baltimore Sun.

Mahmoud’s valiant run in the Guineas did little to enhance his reputation in either the Aga’s stable or among race goers. The British press abounded with articles disclaiming the colt’s breeding, since to carry two speedballs — The Tetrarch and Mumtaz Mahal — in his family suggested speed over stamina, while his sire, Blenheim II, had been slow to find his form at three despite his Derby win. And then there was the matter of his coat colour: only two other greys, the colt Gustavus(1818) and the filly, Tagalie (1909), had ever won a Derby. Little thought was given to the fact that grey thoroughbreds were a minority, making their chances of getting the same number of serious Derby horses statistically impossible.

It was Frank Butters who won the “jockey wars” for the Derby, placing Gordon Richards in the saddle on the fancied Taj Akbar, with Smirke relegated to the Aga’s “third stringer,” Mahmoud.

The gorgeous TAGALIE and her filly foal MABELLA pictured here in 1915. As a filly, TAGALIE had won both the Epsom Derby and the 1000 Guineas, both in 1912.

Derby day was colourless and cold, with a very hard turf surface that would finish Pay Up, who came home lame and caused Lord Astor to withdraw a colt that many considered the best of his generation, Rhodes Scholar (1933). But as it turned out, the course was a gift for Mahmoud. Charlie Smirke, who had said with bravado that he would win and beat arch-rival Richards on Taj Akbar (who finished second) was in tears because, it seemed, no-one had believed in his abilities either. Here’s what the winning jockey had to say:

“…There is only one way to tell you the story of my second Derby victory., and that is from the very beginning — from the time when I had my choice of mounts. I was not asked to ride Taj Akbar and perhaps that was lucky for me. But between the Aga Khan’s two other horses, Mahmoud and Bala Hissar, there was never any doubt. I told Mr. Butters, the trainer, ‘I want to ride Mahmoud; I don’t think the other has a chance.’ And how I laughed when people kept on saying ‘Mahmoud cannot stay.’ I knew he could and Steve Donoghue…settled the matter. ‘Charlie,’ Steve said to me, ‘ You’ll just about win the Derby’ and he told me how he would ride him. When Steve tells you things like that and how he would ride at Epsom, a wise jockey listens.”

Of course, that was only part of the story. The rest was that the ground suited Mahmoud so much that he only really needed a jockey coming into the home straight. And when Smirke asked him, the little grey colt answered.

HH the Aga Khan III shows his delight as he leads his Derby winner in. TAJ AKBAR had come in second.

Here’s footage of Mahmoud’s Derby (with sound). Just follow the link and CLICK on “CLICK 1 of 1”:

http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist//BHC_RTV/1936/05/28/BGX407212133/

Another film clip, this one showing the Aga Khan meeting Mahmoud after the win. Just click on 44592 in the red box on the site:

http://www.efootage.com/stock-footage/44592/Mahmoud_Wins_The_1936_Epsom_Derby/

Other than the Aga and his team, the response to Mahmoud’s Derby win was really rather negative. Having read for weeks before the big day that the little colt would never stay the distance, both punters and racing fans, not to mention the great British turf writers of the day, were horrified to see Mahmoud charge up, leaving the likes of Taj Akbar, Bala Hissar, Pay Up and the American colt, Boswell, in his slipstream. Not only did he win, but Mahmoud’s time was the fastest in the history of the race. It is a record that will likely stand forever, given the difference in the surface at Epsom from 1936 to the present. Others disputed (and still do today) whether it was the horse or the turf that accounted for the record time:

” … Prior to Mahmoud’s Epsom success, there had been a generally held opinion that the grey thoroughbred did not, and even could not, possess sufficient stamina to win races beyond a mile…The supposition was founded less on biological or genetic grounds than on the fact that grey horses simply did not win Derbys…The author has no intention, at this point, to make out a case, either way, for the grey…as a stayer or non-stayer. He is nevertheless entitled to express a personal opinion regarding Mahmoud, which is that he was lucky to have had unusually firm ground over which to race, and that he might never have won had the going been soft, or even yielding.” (The Derby Stakes: A Complete History From 1900-1953 by Vincent Orchard)

MUNNINGS’ gorgeous painting, “SADDLING MAHMOUD FOR THE DERBY,” was turned into a British stamp in 1936 after the colt’s Derby win.

Mahmoud’s next appearance was in the St. James Palace Stakes, where he met up with a colt named Rhodes Scholar for the first time. Rhodes Scholar was a son of Pharos and the influential Lord Astor was considered by many to own THE colt of the season, Mahmoud aside. The Aga’s plucky pony was beaten a good five lengths by Lord Astor’s beautifully bred colt. Some blamed the defeat on Mahmoud’s not having had time to recover from the Derby, but they were a minority. The prevalent view was the one reflected below:

After the St. James Palace, Mahmoud was found to have cracked heels and was given a rest until the fall, when he reappeared for a final time in the St. Leger. Entered were Rhodes Scholar and William Woodford’s Boswell, together with a field of at least ten other horses. According to the Evening Post, Mahmoud was one of the favourites. However, although he produced his run in the final stretch it was too little too late and the Derby winner finished third behind Boswell, who won it, and another colt named Fearless Fox (1933). The much touted Rhodes Scholar was never a factor.

MAHMOUD comes at the leaders, BOSWELL and FEARLESS FOX, close to the finish of the St. Leger. However it was the Woodward colt who got home first, followed by FEARLESS FOX. In the final start of his career, MAHMOUD finished third. Although he came out of the race with four cracked heels, it was the opinion of Frank Butters that the distance had been the real obstacle.

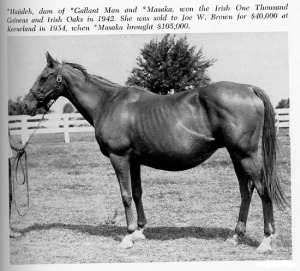

Following the St. Leger, Mahmoud was retired to his owner’s Egerton Stud in Newmarket, from where, in 1939, he bred the champion fillies Majideh and Donatella II. Majideh went on to become the dam of the champion Irish filly, Masaka (1945) and even more famously, of Gallant Man, whose pedigree was rife with the influence of Mumtaz Mahal on top and bottom. Donatella II became the dam of Frederico Tesio’s Italian champion, Daumier (1948), who won the 1951 Derby Italiano, the Gran Premio del Jockey Club Italiano, the Gran Criterium and the 1951 St. Leger Italiano. As a sire, Daumier got champions in Italy and the USA. But it was in America that Mahmoud would make a lasting impact, although he was lucky to arrive there in one piece.

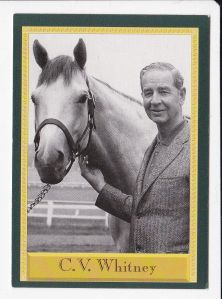

With the outbreak of WWII, the Aga saw fit to accept a bid of $84,000 from an American consortium, headed by Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, for the purchase of Mahmoud. The year was 1940. However, when the stallion showed up dockside to be boarded for his transatlantic voyage, the captain refused to take him, on the grounds that the required documentation was incomplete. The ship was subsequently torpedoed in the Atlantic. However, the ship that carried the stallion to Whitney’s stud farm in Kentucky managed the crossing without incident.

By 1946, Mahmoud had made it to the top of the North American sires list and in 1957, he headed the broodmare sire list, even though trainers like Max Hirsch had initially criticized Whitney for purchasing a stallion whose bloodline he thought would never fit with the Whitney broodmares. But Whitney’s plans were sound, since the Mahmoud genotype was found to work extremely well with, among others, mares who descended from Fair Play. Mahmoud’s progeny tended to be precocious and sound. As importantly, they won on dirt or turf. As success followed success, American breeders reconsidered their early response to Mahmoud’s potential, since the best of his progeny demonstrated both stamina and speed.

Breeders soon flocked to MAHMOUD. Here’s a shot of champion GALLORETTE (1942) with her MAHMOUD filly, GALLAMOUD (1952). The filly went to Ireland where her son, WHITE GLOVES2 (1963) won the Irish St. Leger as well as three other Irish stakes.

Although Mahmoud produced seventy stakes winners, including First Flight (1944), Oil Capitol (1947), Cohoes (1954), The Axe II (1958) and Vulcan’s Forge (1945), it was as a BM sire that he stamped the modern thoroughbred.

Most prominent –and their names can’t help but dazzle — was Almahmoud (1945), one of the greatest matriarchs of all time and dam of the brilliant Cosmah (1953), who produced Halo (1969) the sire of Sunday Silence as well as Queen Sucree, the dam of Cannonade; the Blue Hen mare Natalma (1957), produced the most dominant sire of the second-half of the twentieth century in Northern Dancer (1961), as well as the brilliant HOF inductee Tosmah (1961). Grey Flight (1945), the dam of 9 stakes winners and the foundation mare of family 5-f who produced What A Pleasure (1965), Bold Princess (1960) and 1963 broodmare of the year Misty Morn (1952) was still another famous daughter of Mahmoud. But the list of Mahmoud’s influential daughters doesn’t end here by any means. Three others who made a huge impact were: Boudoir II (1948) the dam of Your Host, who sired the mighty Kelso (1957), as well as Flower Bed (1948), a Blue Hen mare whose daughter, Flower Bowl (1952), was the dam of Graustark (1963), His Majesty (1968) and the incomparable Bowl of Flowers (1958); Mahmoudess (1942), whose accomplished son Promised Land (1954) was the dam grandsire of champion Spectacular Bid (1976) and the BM sire of Skip Trial (1982) who, in turn, sired the fabulous Skip Away (1993) ; and Polamia (1955), the dam of Grey Dawn II (1962) — the only horse to ever beat the mighty Sea-Bird II (1962) — who became the leading BM sire of 1990 and BM sire of 125 stakes winners during his career at stud.

PROMISED LAND by Palestinian (1946) ex. Mahmoudess on track. His bloodlines would flow into the champions SPECTACULAR BID and SKIP AWAY.

On September 8, 1962, Mahmoud died at the age of twenty-nine. He was buried in the equine cemetery on C. V. Whitney’s farm, which is now part of Gainesway.

Upon his death, a touching statement was issued and reprinted in the Thoroughbred Record (later to become the Thoroughbred Times):

“Mahmoud was very much an individual and he seemed to delight in being one. One of his idiosyncrasies was that he refused to be ridden across the Elkhorn Creek bridge though he was willing to go when led. Those of us who have grown fonder of Mahmoud with each of the passing years will miss him more than words can express…He knew human affection but he did not exploit it. He was never too preoccupied to walk to his paddock fence to receive a pat. He was kind and gentle, uncomplicated; any living thing was allowed in Mahmoud’s paddock.” (Whitney Farm personnel, as recorded in The Thoroughbred Record, on the death of French-bred Epsom Derby winner Mahmoud)

Because of the enormous genetic influence of his daughters, today Mahmoud is represented in the pedigrees of some very powerful mares, including Zenyatta, Rachel Alexandra, Havre de Grace, Black Caviar, Kind (dam of Frankel), Balance, Winter Memories, Zarkava, Royal Delta and Danedream. And of the top ten colts on the Derby trail presently (Steve Haskin’s Derby Dozen for March 10, 2014) all carry at least a single Mahmoud influence.

Of course, the little grey stallion who got so little respect during his racing career cannot have a direct influence on either the speed or stamina of his descendants today, as he rests too far removed in most of their pedigrees. But rest assured that Mahmoud, as one of their greatest ancestors, certainly whispers in their blood.

Kelso, the 1964 Aqueduct Handicap:

Sunday Silence, Japan’s supreme sire, in the 1989 Breeders Cup Classic:

“Skippy” — the great Skip Away — winning the 1997 Breeders Cup Classic under jockey, Mike Smith:

Frankel in the Queen Anne Stakes, June 2012

Black Caviar: 25-win compilation

On the 2014 Derby Trail: California Chrome (who carries a double dose of Mumtaz Mahal, with both Nasrullah and Mahmoud in his female family) wins the San Felipe

ADDITIONAL NOTES

* The Honourable George Lambton had been a jockey and competed in the Grand National before moving on to become a leading trainer in England in 1906, 1911 and 1912. He won the Derby and the St. Leger with Hyperion. His book, Men and Horses I Have Known, published in 1924 remains a racing classic.

For those interested in reading more about The Tetrarch, his daughter Mumtaz Mahal and the history of greys in thoroughbred racing, please see an early post here on THE VAULT about Black Tie Affair: https://thevaulthorseracing.wordpress.com/2011/02/09/black-tie-affair-for-michael-blowen/

SOURCES

Baerlein, Richard. Shergar and the Aga Khan’s Thoroughbred Empire. London: Michael Joseph, 1984.

McLean, Ken. Designing Speed In The Racehorse. Russel Meerdink Company: 2006

Mortimer, Roger and Peter Willett. More Great Racehorses Of The World. London: Michael Joseph, 1982.

Orchard, Vincent. The Derby Stakes: A Complete History From 1900-1955. London: Hutchinson, 1954.

Steve Haskin’s Derby Dozen (March 10, 2014)

Tesio, Frederico. Breeding The Race Horse. London: J. Allen and Company, 1958

Willett, Peter. The Classic Racehorse. London: Stanley Paul, 1981.

Reines-de-Course: Almahmoud @www.reines-de- course

Horse-Canada: Broodmare Power In Pedigrees @ horse-canada.com

On The Turf: Short Story: Charlie Smirke (February 12, 2009) at ontheturf.blogspot.ca

The Evening Post, “Third Grey To Win” (May 28, 1935)

— “Another Champion? Aga Khan’s Champagne” (October 10, 1936)

— “The Two Thousand: Pay Up’s Narrow Win” (May 26, 1936)

— “The Derby Winner: Breeding of Mahmoud” (May 30, 1936)

— “Mahmoud’s Last Season” (July 3, 1936)

— “Surprise Result: St. Leger Stakes” (October 7, 1936)

— “The Small Horses Best” (July 14, 1936)

The Straits Times, “Mahmoud’s Jockey Tells How He Won The Derby” (June 5, 1936)

NOTE: THE VAULT is a non-profit website. We make every effort to honour copyright for the photographs used in our articles. It is not our policy to use the property of any photographer without his/her permission, although the task of sourcing photographs is hugely compromised by the social media, where many photographs prove impossible to trace. Please do not hesitate to contact THE VAULT regarding any copyright concerns. Thank you.