I have wanted to write about this great thoroughbred since THE VAULT first opened its doors, but the available information about KINCSEM was scarce and, well, boring…..

Then three great finds and one great “horse source” changed everything. The source was the fabulous website, COLIN’S GHOST ( http://colinsghost.org ) which I read with devotion. Its writer recommended a book called “STEP AND GO TOGETHER” by B.K. Beckworth (1967: A. S. Barnes & Co., Inc.), which I promptly hunted down on abebooks.com (international online bookseller who offers just about everything in print @ reasonable prices). “STEP AND GO TOGETHER” is indeed a little treasure, featuring stories by B.K. Beckwith that first appeared in THE CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED. Within its pages, I was delighted to find Kincsem’s story, which Beckwith wove together using German sources, particularly Philipp Alles, a find that hadn’t been accessible to English researchers since Alles’ account of Kincsem had never been translated into English. (In fact, it may only still be available in German today.)

Another invaluable (book) source proved to be Charles Justice’s “The Greatest Horse Of All: A Controversy Examined” in which I found the information cited here about Kincsem’s race record, annual racing schedules and imposts the great filly carried.

A less sensational, but essential, discovery was a Hungarian to English translator. KINCSEM is a Hungarian thoroughbred and much is written about her in her native Hungarian. The translator helped me to read sources I otherwise would have found inaccessible.

Without these resources, the article would have been much less than it became.

The tale of The Ugly Duckling is a family classic. And the story, of course, is about a swan who was mistaken for a duck and who had to learn that he wasn’t so much an unacceptable duck as he was “a bird of a different colour.” Kincsem’s story is much like the tale of the little cygnet who transformed into a swan. And, as if that’s not enough, Kincsem’s life also features some unique twists on standard heroic myth.

Heroic myths begin with either a confused line of descent or an incident which results in losing one’s parents. In other words, all our heroes/heroines need to be orphaned, in order for them to tell their own stories of courage and resolve. And although Water Nymph’s daughter wasn’t literally orphaned, the dispute over Kincsem’s lineage gives her the kind of muddy beginnings that portend a heroine of mythic proportions.

…The filly was, by all accounts, not much to look at. That was the kind way to say it. Those attending her dam, Water Nymph, despaired: as tiny as she was, the filly foal was downright ugly.

Although some accounts of Kincsem’s birth, notably that of Horace Wade, claim that she was bred in Hungary by Prince Esterhazy, it was in fact a Mr. Ernest von Blascovich who owned and bred her. But something went awry when Kincsem was conceived: her dam had been booked to Buccaneer (1857) but as a result of a misunderstanding, she was covered by Cambuscan (1861) instead. By Newminster (1848), whose dam, the incomparable Beeswing (1833), was a heroine of the turf during her racing days, Cambuscan was a respected stallion. He just wasn’t supposed to meet up with Water Nymph.

Water Nymph (or Waternymph), Kincsem’s dam, was either the daughter of an illustrious mare named Catherina (according to Philipp Alles, quoted in Beckwith) or the daughter of The Mermaid (1833) {according to the majority of English pedigree sites}. However, all the sources consulted do agree that Kincsem’s broodmare sire was the British stallion, Cotswold (1853), who was imported to Germany in 1858.

And it was in this haze of happenchance that the liver chestnut filly foal came into the world on March 17, 1874. She was born at the Hungarian National Stud, whose patrons included the leading horsewoman of her day, the Empress Elizabeth of Austria. The best of the best were bred at the Hungarian National Stud; it was the home of Hungarian thoroughbreds destined for immortality.

The humans surveying Water Nymph and her filly foal clearly believed that beauty was a kind of magic talisman. A magic that Kincsem would seem to have been denied. But whether she was as ugly as some reports contend is a matter of debate, like so many other details of her life.

For example, stories are told of de Blascovich selling the colts and fillies born in Kincsem’s year as a lot, to one Baron Orczy. Orczy took all of them except two — and Kincsem was one of the pair he rejected as “too common-looking.” So it was by still another intervention of fate that Kincsem remained under de Blascovich’s ownership at all.

One tale about Kincsem’s early life that appears consistently in almost everything written about her is that she was stolen by gypsies from de Blascovich’s stable when a juvenile-in-training. The stable was shocked to discover that Kincsem was gone. In fact, she was the only horse missing. She was eventually located by the police in a gypsy camp and when the culprit was asked why he had snatched such a plain-looking horse, he replied: ” Gypsy gold does not chink and glitter. It gleams in the sun and neighs in the dark. This filly may not be as handsome as the others, but she will prove the greatest of them all ” (as recounted by Horace Wade).

Rudolph Valentino in white flannels with a young Horace Wade in 1925. Wade was a child prodigy who went on to author some 800 articles and books on horse racing, He also served as the General Manager at River Downs.

Kincsem’s name (pronounced ‘kink-chem’) reflects the impact that the gypsy’s prediction had on her owner: in translation, Kincsem means “my treasure,” “my precious one,” “darling.” However moved he might have been by the gypsy’s prophecy, de Blascovich started Kincsem at two in Germany, worried that she might bring shame to his stable and reputation. And you couldn’t really blame him:

” She was as long as a boat and as lean as a hungry leopard … she had a U-neck and mule ears and enough daylight under her sixteen hands to flood a sunset … she had a tail like a badly-used mop … she was lazy, gangly, shiftless … she was a daisy-eating, scenery-loving, sleepy-eyed and slightly pot-bellied hussy …” (Beckwith in “Step And Go Together”)

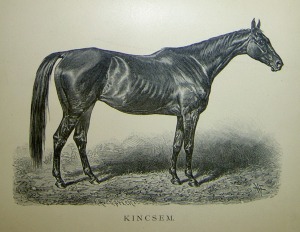

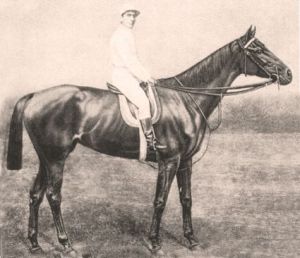

A popular, though less-than-flattering, painting of KINCSEM during her racing years. However, as appreciation for her grows, KINCSEM’s representation by artists and sculptors becomes more flattering. See, for example, her portrayal with trainer HESP, which follows.

Kincsem more or less went to post on June 26, 1876: in the absence of anything vaguely resembling a starting gate, the filly wasn’t forced to fly. So she waited awhile. But when Kincsem finally decided to run, it was all over for the rest of the field: she won by 12 lengths. In her second start, she was sent off against a field that included Germany’s best colt, Double Zero (1873). Not that it mattered: Kincsem won by daylight. (Double Zero would go on to win the German Derby that same year.) She ran eight more races, winning them all, and concluded her 2 year-old campaign with 10 wins in 10 different cities in 3 different countries. The average rest between races was slightly more than 14 days and in her debut year, Kincsem won at distances from 4 f. to 8 f. (Ten would have been considered a reasonable number of races in the late 1800’s; in fact, some of the greats who ran before Kincsem raced as many as 20+ times in their juvenile season. )

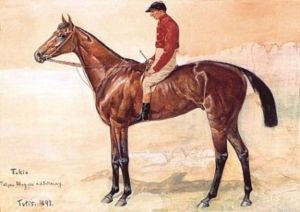

KINCSEM, pictured here with her English trainer, ROBERT HESP. HESP served as a huntsman and a member of the Secret Service in Hungary, as well as a trainer of thoroughbreds.

The filly was quickly becoming a Hungarian notable. No-one cared that she wasn’t as dazzling as Eclipse, who figured in her pedigree, as did many other thoroughbred giants. Kincsem seemed to overflow with personality and her antics won her the love and admiration of all who saw her. The filly put on quite the show for her enamoured Hungarian racing fans in one of her last starts at 2.

Alles’ reports that Kincsem habitually walked to the start looking like “… an old gal with rheumatoid arthritis,” ears flapping and neck bobbing. On this day, she wasn’t really thinking about racing, as her young jockey, Elijah Madden, a native of Manchester, England who rode her for 42 of her races, would later confess: in fact, she was thinking about grazing. At the start, Kincsem found a succulent plot and began to munch away. After repeated attempts to get her into line, the starter gave up and let the field go. Kincsem just stood there, chewing thoughtfully and watching the other horses recede into the distance. Then, suddenly, she seemed to decide that it was time to move and was off after them. She won with ease — some said with a mouthful of grass still hanging from her lip — and the crowd went wild.

As she was led into the winner’s circle, de Blascovich unwittingly added still another quirk to his already-quirky filly’s repertoire by fastening a bouquet of flowers to Kincsem’s bridle. In all of her subsequent races, Kincsem would refuse to enter the winner’s circle until she had received her customary flowers. Philipp Alles’ (in Beckwith) adds: ” On one occasion de Blascovich forgot them and she refused to be unsaddled until he hurried off to buy some {flowers}”

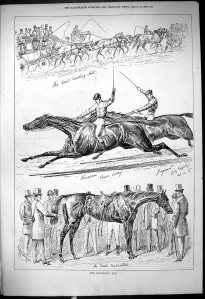

KINCSEM ran low to the ground, as she is pictured here, keeping her head down until she hit the finish, ears whirling like egg-beaters. This manner of running, combined with her long body, effectively cut down on resistance and allowed her to eat up the ground in bounding strides as she accelerated.

Kincsem’s “come from behind” style never really deviated, although she gave a new definition to the term as a result of the mind-boggling advantage she gave her opponents at the start. It’s easy to imagine how she won the hearts of fans across Europe and in the UK when we think about the sheer excitement of watching famous thoroughbreds of today like Secretariat or Zenyatta, who also appeared to favour coming from well off the pace. And, whereas today we would say that thoroughbreds who run this way are always courting potential disaster, covering huge distances to get to the lead never fizzed on Kincsem.

Forty-four races lay before her and Kincsem became a veteran of railroad travels. She seemed to love travelling, watching contentedly from her box as field and town rolled by. Throngs of admirers habitually appeared to greet her and Kincsem acknowledged their affection with a regal dip of her head. Of course, she had her own railway car, which she welcomed with a spirited neigh. But she refused to board it without the company of her two very best friends: a stableboy named Frankie and a cat named Csalogany. In typical mythic tradition, some sources maintain that Frankie was, in fact, Kincsem’s trainer, although extant paintings of the great filly seem to picture Robert Hesp in that role. But there was without question a boy named Frankie with whom Kincsem shared a deep, loving bond and Frankie accompanied her everywhere, caring for her every need. The lad was known to the racing public as “Frankie Kincsem” and when he died, this was the name that appeared on his tombstone.

Csalogany was no less important to the filly than was her human companion. A rather famous anecdote illustrates the point.

When Kincsem disembarked from the ship that had carried her over the English Channel from Dover to France following her victory in the Goodwood Cup, the then-4 year-old filly refused to board her railway car because Csalogany was missing. Kincsem stood on the pier for 2 hours, feet firmly planted and ears pinned back, making it clear that she wasn’t leaving without her feline friend. Finally the cat emerged, tripping down the gangplank. Kincsem turned her head and muttered a greeting, at which point Csalogany jumped up onto her back. Together, cat, filly and Frankie entered the railway car.

The 1878 Goodwood Cup marked Kincsem’s only trip to England and the only race she ran in the UK. Only two horses were prepared to face her: the 7 year-old Pageant (1871) and Lord Falmouth’s Lady Golightly (1874). Both of these were very good horses. Lady Golightly had won the Nassau and Park Hill Stakes, as well as the Yorkshire Oaks, while Pageant had won the Brighton Cup (1876), the Chester Cup (in 1877 and 1878), and the Doncaster Cup the same year he met up with Kincsem.

KINCSEM’s victory in the 1878 Goodwood Cup is reported in the Illustrated London News on August 10, 1878. The drawing depicts a much livelier mare than reports of her appearance as she went down to the start suggest.

As you might imagine, the race was greeted with tremendous enthusiasm. For many, just a chance to see the fabled Kincsem was enough; the press hotly anticipated the meeting between the filly who was undefeated in 36 starts and the mighty Pageant. The build-up was intense and a sobering reminder that it is always the potential defeat of a superstar that oils the sport, giving it a cathartic appeal.

Crossing the English Channel has been the demise of many a seasoned sailor and it was Kincsem’s first — and only — adventure at sea. Predictably, the mare that stepped off the ship at Dover was shaken and sickly-looking. The press seized on this, speculating that Kincsem was doomed even before she set foot on the Goodwood course. Her appearance on the track on August 1, the day of the race, did little to dispel the feeling. Kincsem shuffled to the start, her head hanging so low that her nose seemed to scrape the turf, her neck bobbing crookedly. Thrilled as they were to actually see her, most in the crowd of thousands had no idea that Hungary’s National Treasure always went to the post this way. As usual, she stalled at the start, gazing at the heels of Pageant and Lady Golightly as they sped away. She seemed to be thinking about whether or not the race held any interest for her. Then, in a streak rather resembling a thunderbolt, she was off after the leader.

Kincsem won the 1878 Goodwood Cup by a solid 3 lengths, going away. At first, the crowd was stunned into silence by what they had seen. Then the applause and shouts began, until the roar was deafening. The besotted ran alongside the rail as the filly returned to the winner’s enclosure, getting as close to her as they possibly could. Kincsem, who always seemed to know when a race was over, just as she seemed to calculate how far to let the other horses run before she went after them, pulled herself up and headed back to the place where she would (of course) be presented with a bouquet of flowers by her delighted owner.

It is unclear whether or not His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales was in attendance at Goodwood on the day, but the claim that he attempted to buy Kincsem after her victory may, indeed, be true. According to Philipp Alles, this is indeed the case. But Ernest de Blascovich refused, telling the future king, ” If I sold Kincsem I would not dare return to my native soil.”

The Goodwood Cup race, as depicted in the August 10, 1878 ILLUSTRATED AND DRAMATIC NEWS. The artist took licence with the depiction of the race: there is no evidence that KINCSEM was ever touched by a whip.

Filly, cat, Frankie and the rest of her entourage went on from Goodwood to France, where Kincsem annexed the Grand Prix de Deauville. Her remaining thirteen races in 1878 were run in more familiar settings: Austria (5 times), Hungary (7 times) and Germany once. According to Charles Justice, in his book The Greatest Horse of All, Kincsem had had an average of 13.07 days rest between the 15 starts she made as a 4 year-old, winning 11 of her starts by an average of 2.45 lengths, distancing the field 3 times and cantering home once in a walkover. In the Grosser Preis von Baden, she finished in a dead heat to Prince Giles the First (1874), possibly due to the fact that she carried 137.5 lbs. to his 122. German racing rules stipulated that the two face off against one another again to determine the winner: the second time around, Kincsem dismissed Prince Giles by 5 lengths, going away. Throughout 1878, the filly would carry an average of 144.9 lbs. — an incredible burden by modern weight-for-age standards. And she had stepped up in distance, winning races from 8f to 20f.

This lovely print of KINCSEM shows off her lustrous liver-chestnut coat, massive chest and powerful hindquarters.

Although a consummate traveller at this point, Kincsem was as fussy about certain rituals and traditions as might be expected of a thoroughbred Queen. Other than what’s already been acknowledged, it seems the filly would only eat the food and drink the water from her home, Tapioszentmarton, when she was on the road. At Baden-Baden on one occasion, Kincsem didn’t drink for 2 days because her home water supply had run out. Desperate, someone discovered a well in a town near Baden-Baden where the water had the same earthy taste as the water from the farm. (We’re betting that “somebody” was Frankie.) At any rate, much to everyone’s relief, Kincsem consented to drink it. To this day, that well carries the name “Kincsem’s Well” and is a treasured Baden landmark.

1879 was Kincsem’s final racing year. The mare went undefeated in 12 starts, 3 of which were walkovers, winning at distances from 12f to 18 f. The lowest impost she ran under that year was 136 lbs., with the heaviest 168 lbs., giving her an average of 153.3 lbs. to carry. An unbelievable weight by any standards.

Kincsem ended her career on the turf undefeated, with 54 wins in as many starts, including 3 consecutive wins in the Grosser Preis von Baden and an equal number in the Hungarian Autumn Oaks, which was her final race.

In retirement, Kincsem proved a very successful broodmare, only adding to the legendary status that Europe and particularly her homeland had conferred upon her. She produced 5 foals in all, including the filly Ollyan Nincs (1883), winner of the Hungarian St. Leger and the colt Talpra Magyar (1885) who went on to become a very successful sire. Ironically, both were by Buccaneer, the stallion Kincsem’s dam, Water Nymph, had been booked to (but never saw, going instead to Cambuscan) on the day that Kincsem was conceived. A third offspring, also by Buccaneer, was the filly Budagyongye (1882).

Kincsem’s daughter, BUDAGYONGYE, by BUCCANEER, was very influential in assuring KINCSEM a place in modern-day thoroughbred racing. On the turf, she faced colts to win the Deutsches (German) Derby and ran third in the Austrian Derby.

SEVENTH BRIDE (1966), who descends from BUDAGYONGYE, won the Princess Royal Stakes at Royal Ascot. One of SEVENTH BRIDE’S daughters, the filly POLYGAMY (1971) won the Epsom Oaks and the Ascot 1000 Guineas.

ONE OVER PARR (1972) was another descendant of BUDAGYONGYE. She won the Chesire and Lancashire Oaks. Her son, TOM SEYMOUR (1980) by GRUNDY (1972) was a multiple stakes winner in Italy.

Kincsem had 2 other foals by the British stallion Doncaster (1870): a colt named Kincs-Or (1886) and her last foal, a filly named Kincs (1887). The former was an impressive stakes winner and American interests were mulling over his purchase from de Blacovich when the 3 year-old was found dead in his stall.

Shortly after the birth of Kincs, Kicsem sufferred a severe bout of colic. Less than a day later, the champion was gone. And like everything else about her life, even her untimely death was marked by the kind of “sign” one expects to find in a fairy tale or myth: Kincsem died in 1887 on March 17, the same day on which she was born. A circle had closed. But if there was an augury in such an odd coincidence, it might well be that, like a circle, the spirit of Kincsem had neither beginning nor end.

Hungary lost more than a great thoroughbred when Kincsem died: they lost a quirky and majestic figure who had raced right into their hearts. In her homeland, her passing was officially mourned for three days. Flags stood at half-mast and the borders of Hungarian newspapers were framed in black. And, as fate would have it (and depending on the source), either trainer Robert Hesp or Frankie, her beloved friend, died 39 days after Kincsem.

As a way of assuaging their grief, Hungarians set about punctuating the life and times of their beloved. Hungary boasts a Kincsem Park, a Kincsem Horse Park, numerous hotels and even a golf resort that carries the champion’s name. Kincsem’s skeleton is on display in the Hungarian Agricultural Museum. And statues were erected in her honour, the most famous of which stands in Budapest. As far away as America, Kincsem was remembered: another statue of her stood at the entrance to Keeneland’s walking ring for many years and a smaller bronze statue still inhabits the Chandelier Room of Santa Anita.

As befits a legend, Kincsem endures despite the ravages of two world wars. Although she only had five foals, one of whom died at three, the remaining four — one colt and three fillies — produced offspring that guaranteed Kincsem’s legacy.

The majority of Kincsem’s descendants were bred and raced in Europe. Their numbers are large and include exceptional individuals like Seventh Bride, Polygamy, Tom Seymour and One Over Parr (mentioned above), as well as Viglany (1900), Dicso (1906), Tokio (1892), Caplan (1953), Djurdjevka (1937), Morpeth (1903), Vaduva (1955), Sikar (1928), Well Made (1997), Welluna (1996), Wicht (1957), Well Proved (1980), Napfeny (1896), Miczi (1910), Bank (1945) and Waldcanter (1956).

The German champion, WICHT (1957), winner of the Deutches St. Leger, Grosser Preis Von Nodrheim-Westfalen and the Hansa Preis descends from KINCSEM’S daughter, OLLYAN NINCS.

Although America lost out on acquiring Kincsem’s son, Kincs-Or, her bloodlines found their way to these shores through the mare La Pastorale (1955) who was imported to California by a Major Pauley. And while La Pastorale failed to make much impact as a broodmare, Tarfah (2001) an American-born daughter of Kingmambo (1990) traces back to Kincsem’s daughter, Budagyongye, on her tail female. And Tarfah is the dam of the 2012 Epsom Derby winner, Camelot (2009), a colt brilliant enough to inspire hopes of the first British Triple Crown since Nijinsky (1967) in 1970.

It seems fitting that the breath of an Immortal should find its expression in Camelot.